A little back-story first…

For most of its history, the music industry made the majority of its revenue from the marketing of singles. Napster hobbled that ability in 1999 by providing free and easy access to MP3 files of individual tracks.

Through the RIAA, the major record labels (Warner, Sony, Universal) managed to shut down Napster in 2001 but other P2P file-sharing apps soon replaced it – Limewire, Kazaa, etc.

To combat this and move into the digital age, the major labels struck a deal with Apple in 2002 to populate the soon-to-launch Apple Music Store with the vast majority of their catalogues.

Unfortunately, in that deal with Apple, the major labels screwed themselves and every other label or artist who followed by allowing Apple to dictate how much each a single track was worth. This was an inversion of the traditional supply & demand model in which production dictates the value of a product; sales and distribution do not. (In the traditional model, if a store could not afford the wholesale price of a product, they didn’t buy that product.)

Likewise, the early days of YouTube were fraught with copyright infringements. It quickly joined the ranks of the P2P file sharing apps as a widely-used platform for infringing copyrights. And the most infringed type of content on YouTube was – and still is – music (just as it was on P2P apps.)

Under pressure from the major record labels, Google introduced the ContentID system to YouTube in 2007. This allowed copyright holders to be able to claim their illegally uploaded content on the platform.

YouTube users could still infringe upon copyrights but the labels were given the ability to track, remove, or monetize the content that infringed upon their copyrights. ContentID could – they said – analyze the audio waveform of any upload, compare it to the waveforms of copyrighted content it had on file, and apply the copyright holder’s desired policy – track, remove, or monetize.

The major record labels manage catalogues consisting of millions of individual tracks. To them, ContentID meant a new revenue stream that could be automated, avoiding the many thousands of hours of labour per year that would constantly be required to manually dig through YouTube to flag copyright infringements for removal. (I know because I’ve manually dug through YouTube to flag a few thousand copyright infringements.)

While all this was occurring, Google had brought the Android mobile device to market and opened a music streaming/download service for Android devices. This music service became part of Google Play in 2011 – it was their version of the iTunes Music Store.

The TL;DR is this:

- There’s massive amount of copyright infringement on YouTube;

- The 3 major record labels (whose combined content receive most of the views on YouTube) are happy to just automate themselves out of that conundrum with monetization policies;

- DSPs (digital service providers) like Google and Apple set the price they pay out for the products that make up their supply of content; and,

- Since 2011, Google has operated two completely distinct music streaming platforms – YouTube and Google Play.

2017-2018

In April 2017, I was hired as a label manager by Play Records, an indie dance/electronic record label based in Toronto. One of the reasons for my hiring was my expertise with SaaS platforms such as YouTube, SoundCloud, and web-based media in general. Prior to my hiring, no one at the label had paid much attention to brand development on these platforms, where many music listeners go to hear and discover music.

Most of the Play Records catalogue of 1000+ tracks is underground and/or club music, not the kind of content you’d likely hear on the radio. However, the label was fortunate to have several earlier works of an artist who became a global major label artist, deadmau5. His works enjoy consistent activity in the market that I’m able to measure.

One of the first things I noticed when I began administering our catalogue was that, in addition to our own uploads of tracks from our catalogue to our YouTube channel, there were several thousand illegal uploads. I found ~450 illegal uploads on a manual search for one track alone, Faxing Berlin.

In order to monetize, track, or takedown copyrighted music content, the music needs to be registered with YouTube’s ContentID system.

Our catalogue is fully registered with ContentID via our distributor’s delivery system to YouTube, among many other DSPs. Our distributor keeps a record of all the claims triggered by ContentID and monetized, for all the tracks from all their client labels. So they were able to provide me with a list of all the illegal uploads of Track X on which we were already monetizing. Their list had ~350 uploads.

My list of ~450 manually discovered infringements (i.e. the top 450 correct search results) only shared 4 items with our distributor’s list of ~330 being monetized. Once we had claims on those ~446 videos I’d found, Google didn’t pay us for all the revenue and platform value they’d been generating off our content for 7 years. And unfortunately, based on the price that YouTube determined it would pay suppliers for each stream and based on the view counts of those illegal uploads, the loss of revenue did not pass the threshold required for us to take worthwhile legal action against Google.

In other words, YouTube pays so little to its suppliers that the revenue that YouTube essentially stole from one of its suppliers is less than the cost of going after YouTube to recoup that stolen revenue. YouTube is the dollar store of the music industry.

Because illegal uploads are very rarely packaged with any marketing structure (i.e. links to go buy the product, listen to more music from that artist/label), and because YouTube pays out to content providers the smallest fees of any music platform, and because we’re an indie label that’s in the business of introducing new talent, the monetization we’d receive from all the illegal uploads of our catalogue on YouTube is far less valuable to us than being able to direct viewers to more or similar content to which we’re trying bring attention (i.e. new artists, new music.)

The revenue is so low anyway that it’s the eyeballs that are more important to us than any revenue generated by those eyeballs.

So we decided upon a policy that we would issue takedowns of all illegal uploads so that traffic to our content would be restricted to our uploads of that content where we could offer viewers some options to consume more of the artists whose works we release, rather than what an algorithm feeds them.

Over the course of 3 weeks, I manually issued around 2000 DMCA claims of illegal uploads, unlicensed remixes, and mash-ups, with an order to takedown. YouTube has a form that allows users to submit up to 10 URLs at a time. With each claim, I’d receive a confirmation email in our Gmail account.

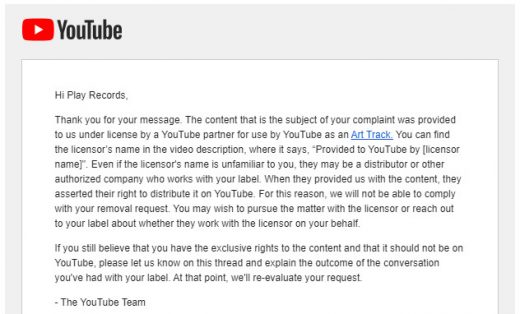

Then I started to see a receive rejections from YouTube. They were refusing to remove our copyrighted property from their platform because it had been provided by one of their partners…

Upon inspection of the video descriptions of the auto-generated album art videos (Art Tracks), I counted many other distributors (Believe, Kontor, Ingrooves, base79, among others) who were distributing our property without a license to do so. All told, there were around 600 illegal uploads that YouTube had (or would have) refused to remove.

Here’s an example of an auto-generated Art Track: https://youtu.be/34snASaX5uE

What I eventually discovered was this:

Years ago, we had licensed tracks from our catalogue to other labels (Sony EMI, Ultra, and sundry indie labels) to be released on compilations. Those licenses had all since expired or were restricted to physical sales (vinyl or CD.) But because they hadn’t been removed from each label’s catalogue management systems, they were added to their respective distribution systems as the industry shifted towards streaming. Because they’d rather do things the easy way (automated) than the right way (manually), those labels and their distributors illegally supplied our property to DSPs to be exploited digitally.

One of those DSPs was Google Play, which is the source of content for all of YouTube’s auto-generated Art Tracks. These Art Tracks were developed specifically for use on Google’s new music platform, YouTube Music.

Keep in mind that, in terms of the software, YouTube Music is not a separate entity from YouTube. It is merely a sub-domain of YouTube that employs a different cascading style sheet to display a different web design and layout. Everything else behind the scenes – all the code and algorithms, all the functionality – is all just YouTube. The only difference is the design and layout. If you loaded a video at music.youtube.com and then replaced the “music” part of that domain name with “www”, the same content loads within the traditional YouTube design and layout. They are the same platform.

An example: the 2 links below are the exact same page, but the one with the “music” prefix on the URL simply loads in a different design and layout into which it brings the exact same content and functionality.

Link with music. prefix / Same link but with www. prefix

Here’s a blog post that our attorney shared with me at the time that I was starting to discover all this. It provides some additional background to Art Tracks.

In August 2018, I started seeing Art Tracks of works from our catalogue, but with our own label and distributor listed as YouTube’s content suppliers.

Earlier in 2018, our distributor began offering YouTube Art Tracks as a new distribution program and all labels represented by our distributor were opted-in to that program by default. However, when I inquired into this, our distributor informed me that we could still opt out. At first, I directed our distributor to opt us out of YouTube Art Tracks but then followed up with a direction to hold while we discussed the matter with our attorney.

Then, on 3 Aug 2018, I get an email from our distributor’s content manager that included the following:

FYI, to remove your tracks from YouTube Music means also removing them form Google Play. We are contractually obliged to make the Google Play releases available for YouTube Music.

And on 7 Aug 2018, after more of my inquiries into this, from the same content manager:

Every supplier that has an agreement with YouTube for monetisation is required to provide the content as art tracks. YouTube use their Google Play feed to create the art tracks.

On 10 Aug 2018, from our distributor’s VP of Artists, Content & Labels:

Google/YouTube do try to tie everything in. When any asset delivered for monetisation the partner is required to provide an art track.

I believe this is across the board as i know some labels who were direct with YouTube had issues as they were being forced to provide this.

The reason this is linked to Google Play is because the delivery is facilitated through the GP deliveries. With GP we’re waiting to hear back to see if we can deliver separate rights or issue takedowns.

In answer to your question you can’t monetise 3rd party content on YouTube without delivering an art track form our understanding.

So we then had to ask ourselves the question, “Is our Google Play revenue worth being screwed over by Google’s Art Tracks on YouTube?”

At the time, our Google Play revenue comprised approximately 9% of our total revenue from streaming and downloads. We decided that we could not take a 9% hit to our total stream/download revenue.

Essentially, our official content that we administer on our YouTube Channel is now – and has been for at least the past 2 years – in direct competition with itself because of this Google policy.

We have no control over what Google does with our property in its right hand (YouTube) for fear of getting slapped by its left hand (Google Play.) This is most certainly antitrust behaviour and, to me, seems an awful lot like outright extortion.

2019 – Present

Though YouTube Music officially launched in 2015, it was not until 2019 that Google began making the platform their primary focus for music distribution.

Starting in 2019, visitors to YouTube could not load any page on YouTube without a popup ad appearing to drive them to subscribe to YouTube Music. In the same year, Google replaced the Google Play app with the YouTube Music app as the default music app on all new Android devices.

Our Google Play revenue has declined every month since we decided we could not afford to lose 9% of our stream/download revenue.

And while we have seen an increase in our revenue from YouTube, the revenue that we receive from YouTube is a little less than one quarter of the revenue we receive for the same amount of streams on Google Play.

In 2019, Google Play streams paid out at £4.01 per 1K streams while YouTube streams paid out at £0.91 per 1K streams. YouTube accounted for 29% of all our streamed content last year but only 12.4% of the revenue from that content.

Even though we complied with their anti-competitive Art Tracks policy, they still managed to fuck us over. I anticipate Google Play will be shuttered within 3-5 years as YouTube continues its mission to gut the music industry.

And this is the inherent conflict of interest in scalability… A platform grows so massive that its delivery systems can only be managed through automation. But automation doesn’t stop to wonder if it’s doing the right thing. Automation doesn’t think to ensure that its suppliers are legally permitted to supply the items it manages. Automation is a steam roller that crushes all the legitimate exceptions to its automated rules.

In 2017/18, it took me 7 months of back-and-forth emails with YouTube to get 4 illegal uploads of Faxing Berlin removed that had been supplied to YouTube by record labels that had no right to supply YouTube with that content. Most of the correspondence from YouTube was automated. When I did get the occasional human (though nameless) response, they just kept feeding me back to the beginning of the automated claim process. In those 7 months, those 4 videos accrued several million more views (on top of the millions they already had.) Millions of potential eyeballs that were rightfully ours were denied to us.

More than 99% of record labels are indie record labels, accounting for 40% of all revenue in the music industry (2017). Every one of those labels is in the exact same position as we are. Whether they’re aware of it or not is another matter.

The only reason we continue to distribute our content on YouTube is preventative damage control: if we don’t, illegal uploaders will. We are only present on YouTube to stifle the copyright infringements that have made YouTube the “success story” that it is. If some kid can’t find a track from our catalogue on YouTube, they’ll illegally upload that track to their own channel. And given my experiences with the failings of YouTube’s ContentID system, we cannot risk relying on automation to manage this revenue stream.

Unless we’re the exception (which is doubtful), there are thousands of independent labels and many more thousands of artists who are losing a shit-ton of revenue because of how YouTube has chosen to do business.